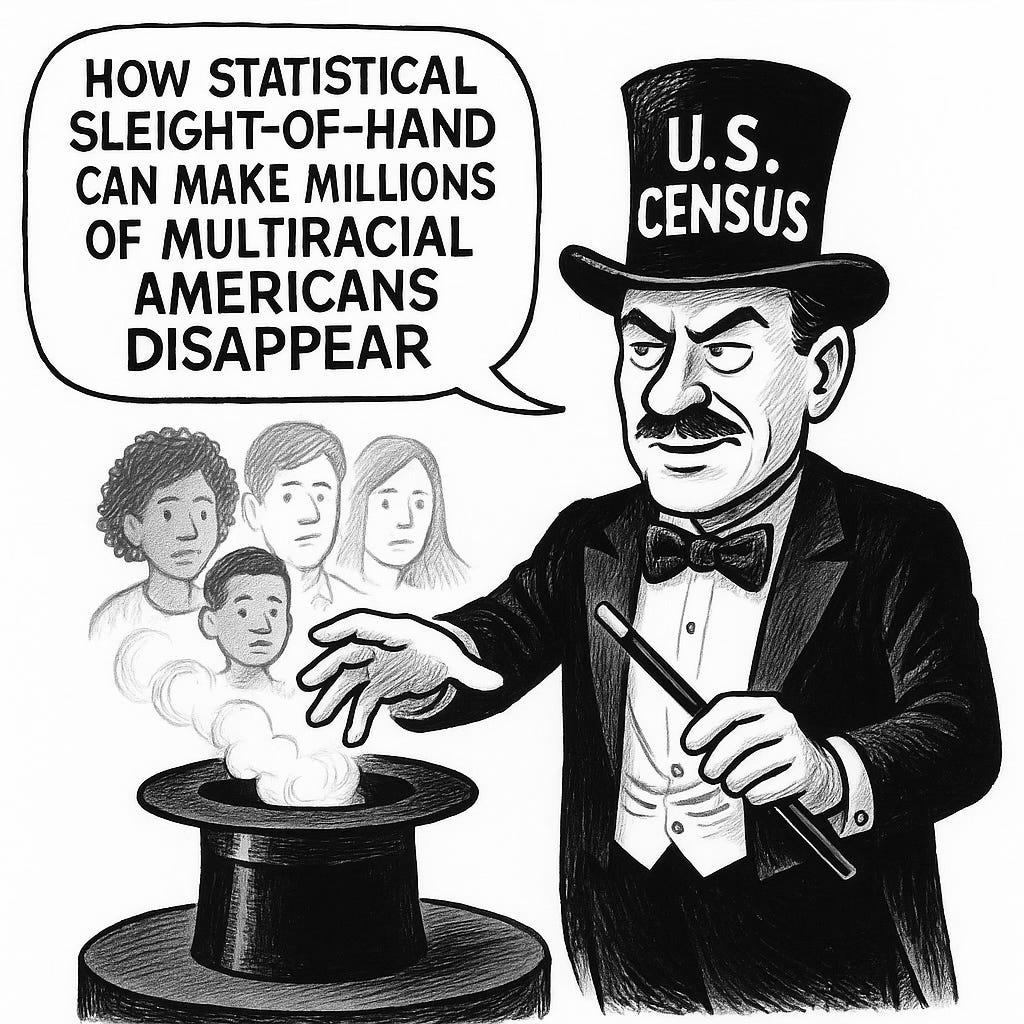

The U.S. Census Bureau’s 2020 Modified Age and Race Census (MARC) uses a statistical imputation process to reclassify people who select “Some Other Race” (SOR) and many multiracial respondents into single-race categories. While self-reported data remains, this method effectively reduces the official count of multiracial Americans by millions, inflating single-race totals—especially “White Alone”—and reshaping public perception of U.S. demographics.

It bears repeating here that, in the second issue of “Lies, Damned Lies, and Statistics,” I reported that, “Since 2012, more white Americans have died each year than have been born — a demographic phenomenon known as "natural decrease."

To today’s point, between 2000 and 2020, “Some Other Race” (SOR) and multiracial (including SOR) identifications grew from 18 million to nearly 50 million (about 1 in 7 Americans), yet MARC reclassification lowered the multiracial share from 14.6% to 4.4% of the population, while increasing the “White Alone” share to 73.8%. Critics warn that using these imputed figures risks downplaying the nation’s rapidly expanding multiracial and multicultural population.

MARC proponents Paul Starr (left) and Christina Pao recently published a report in the Journal, Sociological Science, a piece entitled, The Multiracial Complication: The 2020 Census and the Fictitious Multiracial Boom. 1

Princeton researchers Starr and Pao argue that the sharp rise in multiracial Americans reported in the 2020 Census was largely a statistical artifact caused by an algorithm that reclassified some single-race respondents as multiracial based on their reported national origins.

Comparing 2019 and 2021 survey data, they found dramatic shifts—such as large drops in “white alone” counts among Hispanics and increases in “white and some other race”—that they attribute to this reclassification, not genuine identity changes.

They warn that the method undermines the Census tradition of self-identification, inflates multiracial counts, complicates data comparability, and could create legal challenges in civil rights enforcement.

Evaluating the Princetonian assertions:

1. Core Hypothesis

The authors argue that the 2020 Census “multiracial boom” was largely a statistical illusion caused by an algorithm that reclassified respondents based on national origin write-ins, not on actual self-identification as multiracial.

This is a legitimate research question, but several points suggest interpretive framing anomalies:

2. Inconsistencies & Methodological Gaps

a. Pre- vs. Post-Change Comparisons

They compare 2019 ACS data to 2021 ACS data (skipping 2020 due to COVID disruptions).

While reasonable given pandemic effects, this assumes all observed shifts are due to algorithmic reclassification— but there may be other confounding factors between 2019 and 2021, such as public changes in racial identity awareness or political/cultural shifts.

b. Lack of Direct Testing of Algorithm Impact

They cite examples (e.g., Argentina, Dominican Republic, South Africa) to illustrate misclassification risk, but it’s not clear whether they tested the scale of this effect directly in raw Census microdata.

Without quantifying how many cases fit these examples, they risk overstating their influence.

c. Category Coherence Argument

They claim “Asian-Whites” and “multiple-race Blacks” together make an incoherent category. And yet…

While analytically fair to note heterogeneity, the Census “Two or More Races” category has always been heterogeneous — so the argument assumes a standard of “coherence” that may not have existed in earlier multiracial counts either.

3. Possible Signs of Bias or Framing Effects

a. Use of “Fictitious” in the Title

The word “fictitious” suggests deliberate fabrication, which may imply intentional manipulation by the Census Bureau without direct evidence of political or policy motivation. This risks undermining objectivity.

b. Emphasis on Illusion vs. Interpretation

The authors equate the increase in multiracial counts with being “false,” but they frame the matter largely as an error rather than a definitional or classification shift. This could bias readers toward seeing malfeasance rather than methodological change.

c. It has been proven for years that people do change their racial identity on the decennial Census from one period to the next.

Pew Trust Research2

“Millions of Americans counted in the 2000 census changed their race or Hispanic-origin categories when they filled out their 2010 census forms, according to research presented at the annual Population Association of America meeting. Hispanics, Americans of mixed race, American Indians and Pacific Islanders were among those most likely to check different boxes from one census to the next. The researchers, who included university and government population scientists, analyzed census forms for 168 million Americans, and found that more than 10 million of them checked different race or Hispanic-origin boxes in the 2010 census than they had in the 2000 count. Smaller-scale studies have shown that people sometimes change the way they describe their race or Hispanic identity, but this research is the first to use data from the census of all Americans to look at how these selections may vary on a wide scale.

“Do Americans change their race? Yes, millions do,” said study co-author Carolyn A. Liebler (Photo, left) , a University of Minnesota sociologist who worked with Census Bureau researchers. “And this varies by group.”3 Mike Lakusta (Photo, right), CEO of EthniFacts4, the Texas-based research firm (and collaborator with Nielsen5) said, "Research done by Carolyn Lieber, in conjunction with the US Census, clearly depicts that people do change their racial identity for many reasons, not just due to an algorithmic snafu AND have been doing it for many years."

d. Selective Examples

Using a high-profile figure like Elon Musk to illustrate misclassification could introduce emotional or political overtones. While memorable, it may bias the reader toward viewing the practice as absurd or illegitimate rather than neutrally debatable.

4. Unstated Assumptions

Self-Identification as Gold Standard: They treat racial self-identification as inherently more valid than algorithmic classification, but do not deeply explore the trade-offs — e.g., how to handle incomplete forms, inconsistent write-ins, or cases where respondents use nationality as a racial proxy.

Static Identity View: They imply that racial identity is fixed across time and contexts, which ignores the fact that individuals may reinterpret their identity between surveys, especially amid cultural shifts.

5. Overall Assessment

The research raises important methodological concerns — especially about transparency in classification changes — but:

The claim of a “fictitious boom” is rhetorically loaded.

They assume without full quantification that the observed shifts are primarily algorithm-driven.

Their critique leans toward defending a particular normative stance (“respect self-identification above all”) rather than exploring whether there are scenarios where algorithmic recoding could improve data quality.

6. Conclusion

“White” and “Black” categories in Census data provide some insight into structural inequality and demographic trends, but they are blunt tools. They are shaped by history and law rather than precise anthropology, and they risk oversimplifying — or outright misrepresenting — the country’s racial reality. When individuals misreport (intentionally or unknowingly) or when multiracial identities are recoded into monoracial categories, the data’s ability to reflect the true racial landscape is compromised.

The challenge ahead for the Census and OMB, along with academic researchers, is balancing policy continuity with accuracy in capturing a more fluid, complex, and multiracial society — without erasing reported identities in favor of bureaucratic convenience.

https://spia.princeton.edu/news/research-record-multiracial-complication-2020-census-and-fictitious-multiracial-boom

https://www.pewresearch.org/short-reads/2014/05/05/millions-of-americans-changed-their-racial-or-ethnic-identity-from-one-census-to-the-next/

Liebler CA, Porter SR, Fernandez LE, Noon JM, Ennis SR. America's Churning Races: Race and Ethnicity Response Changes Between Census 2000 and the 2010 Census. Demography. 2017 Feb;54(1):259-284. doi: 10.1007/s13524-016-0544-0. PMID: 28105578; PMCID: PMC5514561.

https://www.ethnifacts.com

https://www.nielsen.com